We sometimes forget it, but America is still a young country. Countries across the oceans have thousands of years of history, thousands of years of myths and stories. The myths that are truly rooted to this land belong to the Native Americans (and they’re even called Native American myths, not American myths; a clear “them” and “us” scenario.) Many of the myths we associate with this country, like the Jack Tales I grew up with in the Appalachian Mountains, are just tales retold from the British Isles. Every person of non-native descent remembers the stories our ancestors brought, not the stories of this land; we have very few of those.

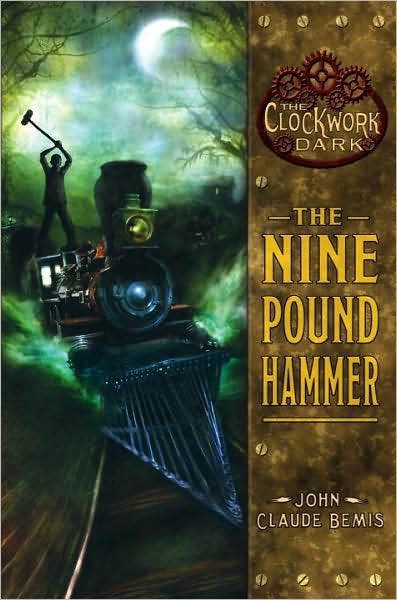

What made me think about it this time is John Claude Bemis’ young adult novel The Nine Pound Hammer. Because America does have myths; they’re just connected to history and renamed tall takes and folklore. We’ve made legendary figures from our founding fathers, the Western settlers, and war heroes. The nine pound hammer, if you don’t get the reference, was the weapon of the mighty John Henry. Legend says the strongman beat a steam-powered hammer in laying railroad ties, only to die after his victory, holding his hammer. The novel The Nine Pound Hammer begins eight years after Henry’s death, which is more mysterious than our legend makes it out to be, and introduces his son, Conker, a giant of a teen working within a medicine show as its strongman.

The story is told from the point of view of another boy, Ray, a twelve-year-old orphan heading to a new town to hopefully find parents with his sister. Their mother is dead, their father gone these eight years, never fulfilling his promise to return to them. His father was a man remembered as bigger than life, with the power to talk to animals and owner of a lodestone, which he gave to Ray before he left.

The book gives a fascinating and magical view of America as a wondrous place, where the tall tales have hints of being real. Upon leaving his sister to give her a better chance at adoption, Ray has an odd encounter with a bear, ending up riding her before being knocked out cold. He’s rescued by Conker an eight-foot tall teen and his companion, a girl named Si who has one hand tattooed entirely in black and an uncanny sense of direction. They take him to their home, a train called the Ballyhoo, which houses a medicine show. Conker and Si are but two of the amazing members of the show, it also includes adults like Nel, the medicine show leader who possesses powerful hoodoo skills, and Buck, the blind sharpshooter, as well as teens in the roles of a fire-eater, a snake charmer, and a half-siren.

This book seems to be in danger of falling into the “D&D” trap, each character filling a role to create the ideal group, but Bemis skillfully avoids this perfect scenario pitfall, letting characters fail as well as shine: just because the sharp-shooter doesn’t miss doesn’t mean he makes the best decisions on what to shoot, for example. Our protagonist, Ray, joins the show as an untalented stage hand and herb gatherer, but he slowly begins to show he has his own special ability. He doesn’t see it yet, but the reader catches on.

The most shocking thing for Ray is finding out that these fantastic people knew his father, and once fought beside him as Ramblers, people with fantastic abilities that became American folklore: John Henry and Johnny Appleseed, among them. Their greatest enemy was the Gog, a man who created machines that ran on human souls. His first machine was the one John Henry destroyed before he died, but the Gog escaped and currently works on another, more terrible machine intending to enslave the minds of millions. He has hunted many of the Ramblers, but a few, like Buck and Nel, survived.

The book is slow in some places, and doesn’t really pick up until about halfway through. One gets a feeling that it’s a set-up for more exciting books to come. (It is Book One of The Clockwork Dark, after all.) While Ray is the protagonist, the book shines most when showing Conker’s story as he is forced to mature and accept his heritage. He begins as a timid giant, at the same time stronger and more frightened than anyone. He shrieks when the snake charmer slips a snake into his room, for example. But he knows who his father is, and once the nine pound hammer comes into his possession, he begins to grow up.

Bemis doesn’t make a lot of mistakes, and his plot elements are carefully planned out. He doesn’t throw things in to see if they’ll stick; he deliberately plots the consequences of each event, even if the effects aren’t completely obvious. A sharp reader will catch some references, and realize that Bemis didn’t just throw something in early on because it sounded interesting. (To say any more would give things away, sadly, but I will say I’m looking forward to Book 2 to see if I’m right about some things.) I can’t ignore the Gog’s wonderful contraptions, including the hoarhound: seven feet of menacing, mechanical, icy terror.

The book could be stronger in some of the characterizations: one character, Seth, is “the mean kid” who doesn’t want to welcome Ray into the medicine show, and we don’t see a lot of depth to him. He seems to be there just to make sure there’s conflict within the medicine show’s teens, but Si’s mistrust of Ray paired with her close relationship to Conker makes more sense than Seth’s arbitrary hatred of the newcomer and adds more to the plot.

Overall, what The Nine Pound Hammer did for me was to bring alive American myth; many of the characters are Bemis’ creation, moving beyond John Henry and Johnny Appleseed, but it works. I could easily hear more about these characters and how their mythological adventures shaped this alternate America. The book also creates a melting pot of mythology: the characters are men, women, black, white, Native, Hispanic, and Chinese. While some may see this as an “After-School Special” attempt at getting a balanced cast, I think it succeeded as a novel working to create new legendary characters. Why doesn’t America have tall tales and myths about every race that moved here? Our country was made from the work, heritage, and yes, myths, of many races, after all. This book reflects the country back at itself, showing the characters larger than life. These characters are being placed in a position to do amazing things, and I think book 1 of the Clockwork Dark was simply setting the stage.

Mur Lafferty is an author and podcaster. She is the host of I Should Be Writing and the author of Playing For Keeps, among other things. You can find all of her projects at Murverse.com.